Teaching kids about (digital) money

This blog post is part of the Finthropology series Digital Human Finance. We present qualitative research to showcase the kind of insights that can come from deeper, human-focused studies and how they can be used to build new sustainable financial solutions. We focus on the story and its potential in each presented publication.

Digital money has altered the ways we learn about money when we are children. Usually, children first learn about money through playing with coins and banknotes (real or play money). Children observe their carers taking money out of their wallets to pay for things, and carers may invite their small children to hand over money to a shopkeeper. Later, children receive pocket money, which they are taught to count and save in a piggy bank. They start to learn the value of money when they calculate what they can afford to buy, and how long they will have to save their money to reach a goal to pay for a new toy.

These days, many of us have stopped using cash altogether, unless we need a coin to use a shopping trolley or to donate to a busker on the street. But young children still primarily use cash—even in countries with low rates of cash usage.

Most parents still use coins to teach their young children about money, dole out pocket money, and pay their kids for completing tasks. How, then, do parents teach their kids about digital money? And how is children’s literacy affected?

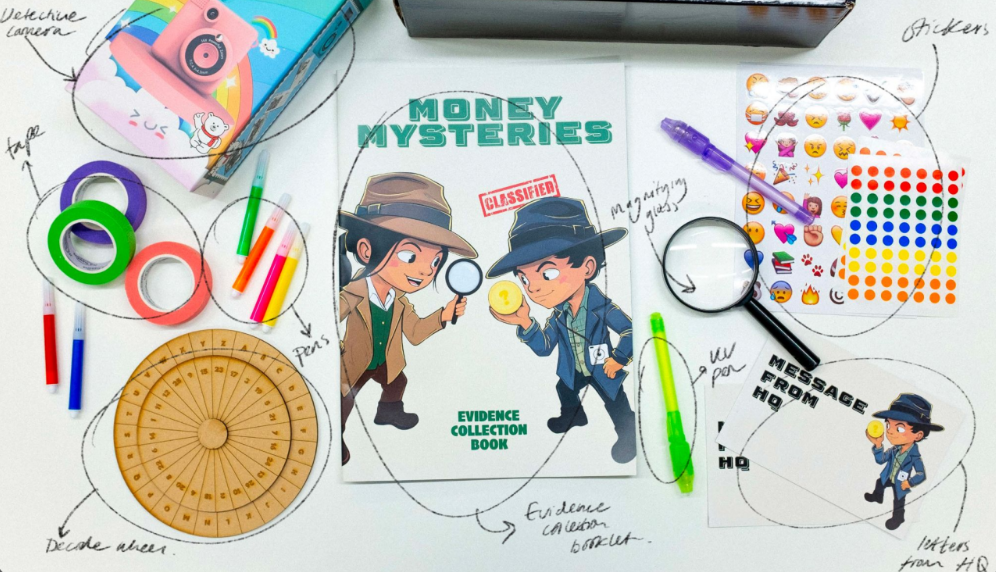

The researchers used this ‘Detective Probe Pack’ in their research on children’s use of money.

These issues were explored by a group of researchers at the University of Edinburgh who conducted research (thirteen children aged 7-12 (in eight families). They used a method called ‘cultural probes’ in which researchers use artifacts to encourage creative and playful responses from participants. They developed a ‘Detective Probe Pack’ that included a ‘Money Mysteries’ activity book, which children filled out with the help of their parents over the course of several weeks. The children were the ‘detectives’, and the researchers were the ‘headquarters’.

The goal of using the activity book was to collect children’s responses to key questions about money, such as: What is ‘real’ money? What was money like in the past versus today? What does money do for you? They also explored different kinds of money, such as tokens and in-game currencies.

Overall, they found that although the children primarily used cash, they had a well-developed sense of what money is, the different forms it can take, and the fact that money’s value stays the same whether it is in cash or digital form. They viewed cash as an ‘old’ form of money, but also felt that it is more ‘fun’ than digital money. They also had a good understanding of coupons and in-game currencies.

Indeed, the researchers note that while adults can find it difficult to explain what ‘real money’ is, the children had a strong understanding of what money is and what it is not. For example, a thirteen-year-old noted that "money stores value and is used to exchange for lots of things", while a ten-year-old said that money is "used to sustain yourself, your house and your family. You can buy things that you need and sometimes a little treat". The children also understood how people get money, with one ten-year-old stating that "adults get paid money if they have a job", and a twelve-year-old commenting that "money is something for trading; if you give somebody money, they give something to you.”

The researchers wanted to explore whether a digital format makes it harder for children to manage money well. While the children in the study mostly used cash themselves, their parents did not. As a result, the children did not see their parents doing common financial tasks like budgeting, paying bills, and so on. These became invisible to kids. They note that such invisibility makes it harder for children to learn about the financial costs of everyday life, and can also make money seem limitless.

The study also showed how the shift from cash to digital occurs in stages. While children under the age of twelve usually do not have mobile phones, they nonetheless start using digital money through their parents’ mobiles. Today, there are many pocket money apps available that parents can use to pay their children an allowance, often with an app and a bank card for the child to use.

Bank offerings include Starling’s Kite and NatWest’s Rooster Money; non-bank offerings include GoHenry and George Junior. Bankaroo is an interesting example as it is primarily a free platform that aims to teach kids about money (offering accounts to both parents and schools), but users can also pay for a premium version that permits transactions such as saving money. Children also learn about value through non-financial apps, such as by playing video games that reward them with coins and other tokens. Thus digital interfaces provide them with similar opportunities to learn about value and making budgeting and spending decisions.

The study shows that the process of using money digitally was highly supervised: parents did not let their children shop online by themselves, and budgets were pre-approved. Some parents had set up a digital pocket money app for their children (such as Go Henry). In some cass,e children had a bank card they could use for pre-approved purchases, such as school lunches or transport. And parents would make online purchases for their children—with the kids paying their parents back in cash they had got as pocket money or as gifts from grandparents. In another case, parents borrowed cash from their child to pay their window cleaner, which they then returned to their child in digital form via a pocket money app.

This hybrid approach to kids’ money management has pros and cons. On the one hand, it provides a transition in which kids can learn about digital money slowly. It can also prove convenient, such as when a child runs out of money and their parents can top up their card remotely. On the other hand, the researchers found that kids were actually more independent with cash as they could manage it themselves, count it to check how much they had left, and decide how to spend it privately. Since the children did not have mobile phones, storing money digitally meant that they did not have this level of control or oversight.

A key difference between cash and digital money is that learning to use money digitally requires different kinds of literacy. With cash, children must be numerically and financially literate in order to make purchases, check change and make budgets. With digital money, children must also be technologically literate, including basic skills in navigating around devices, understanding the interfaces of apps, norms regarding private passwords, and being able to read one’s financial position in, say, a bank account, pocket money app or game.

As children gain more control over devices, they must also be aware of risks like fraud, gambling and software glitches, and they may also need some understanding of the terms and conditions of their purchases. When children start shopping online, they must understand how much they are spending, the conditions of purchase, and how to avoid fraud. They also need to learn about data safety and privacy (NL Times 2023).

Educating children about money, then, is by no means just about money-related topics like spending, saving and budgeting. Instead, financial education is part of a broader program of teaching children about digital engagement, including developing digital skills and an understanding of online safety.

Financial service providers could use information like this to meet children’s needs in payments and savings. Accounts and cards that cannot be overdrawn already exist. Perhaps it would be possible to invent some kind of method or software that would allow children to access their digital money without being a phone with full internet access. Many children already wear kid’s smart watches that allow them to undertake a limited range of activities (such as calling their parents). Adding a way to pay would seem a valuable next step.

We should, of course, also acknowledge that kids are likely to remain embedded in a cash ecosystem for quite some time to come—and that this is a critical aspect of their financial learning.

Andries, V., Wilson, C., Everson, H., McKinley, C. and Elsden, C. 2025. The Secret Lives of Children’s Money: Exploring Children’s Financial Interactions in Transitions from Cash to Digital Monies. Interaction Design and Children (IDC), Reykjavik, Iceland.